Cover Image courtesy of the Jim Seelen Motel Image Collection.

You know, quite often while we’re researching these Motel Monday features, we come across a postcard of a really cool neon sign or an awesome mid-century modern style motel that reminds us of the places we stayed back during the summer family vacations of our youths. As a result, it gets our attention and we start researching the motel a little more to see if there’s a good story in it.

As we dig a little deeper into history of the motel, sometimes we find nothing beyond the postcard. However, sometimes we’re surprised to find that it has an important link to history – not just us our own personal histories of those road trips of yesteryear, but the history of our nation as well.

This is what happened while researching the former Windsor Motel of Summerton, South Carolina. Though its role is rather small in the events that surrounded it, the actions of the Windsor Motel management had a rather profound effect on one of its employees who was part of those events at the time. And since we’re nearing the end of Black History Month, we saw it fitting to tell the story of those events here on Motel Monday.

“The Wheels on the Bus…”

The Windsor Motel was built around 1940 on the southbound side of US Routes 15/301 just outside of Summerton. For those traveling to and from Florida, the motel offered 24 tastefully decorated rooms, steam heat, tile baths, air conditioning, a putting green, and a restaurant. One of the maids employed by the motel soon after it opened was a Black woman by the name of Eliza Briggs.

Eliza had a neighbor by the name of Levi Pearson whose children, Jesse and Piney, walked nine miles each way to the Scott’s Branch School in Summerton every school day. Their brother, Fernando, had to walk seven miles to the Mount Zion School.

When the weather got bad, Levi would put planks across the back of his beat-up old pick-up and drive his kids to school. Eventually, Levi, his brother Hammett, and neighbor Joseph Lemon would save up enough money to buy a used bus to take the Pearsons’ and other local kids to school. In 1946, they bought a slightly better bus, asking for financial donations at weekly meetings to keep the bus filled with gasoline and to take care of its upkeep.

You see, the Pearsons children along with the other kids they took to school were black. And while they were walking or riding in the back of an old rickety pick-up or bus to their school, the white kids of Summerton had 30 brand new buses that took them to school every day. The wheels on the bus do, indeed, go ‘round and ‘round for some better than they do for others.

Levi Pearson and the other Black parents didn’t think this was right. As a result, they asked the county school board for help by giving them money towards gas and repairs for their bus; however, the all-white school board turned them down.

Old School Ways

The school board claimed that the reason they turned down the request was simple: White people made more money than Black people. Thus, they paid more taxes and since White people paid for their own school buses, it would be unfair to have them pay for school buses for Black children, too.

Still, the problem wasn’t only with school buses. The problem was with the schools as well. White children in South Carolina went to public schools for free. Theirs were modern brick schools with new textbooks, water fountains, steam heat, indoor toilets that flushed, gyms, auditoriums, and libraries.

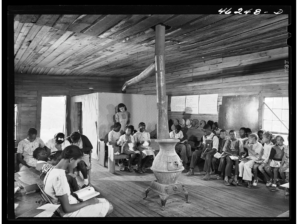

Blacks were taught in basically run-down former hunting and Masonic lodges or cabins next to a local Black church. Blacks had to pay tuition and rent on used textbooks the Whites no longer needed. They brought their own water, dug their own privies, and brought lumps of coal and pieces of wood to add to the pot belly stove.

Indeed, though segregation of schools did not violate the “separate but equal” doctrine of the 14th Amendment, it certainly didn’t grant the equal rights of all races guaranteed by that same amendment.

As a result, after seeking relief from the District Superintendent L.B. McCord and being denied once again, the Black citizens of Summerton decided it was time to take the matter to court. On March 16, 1948 local attorneys Harold Boulware and Thurgood Marshall, filed the case of Levi Pearson v. County Board of Education in U.S. District Court. Unfortunately, their case was dismissed on a technicality involving Mr. Pearson’s paid taxes. His land sat on more than one school district; as a result, the court ruled that Pearson had no legal standing because he paid taxes in District 5 and his children attended school in districts 22 and 26.

Briggs v. Elliott

Thee Black people of Summerton would not be dissuaded, however. In 1949, they obtained enough signatures to petition another trial. On the top of that list of signatures were Harry Briggs and his wife Eliza. And this time, it wouldn’t only be buses they were asking for. This time they were suing R.W. Elliott, the president of the school board for Clarendon County, South Carolina, for total education equality.

The DeLaine, Pearson, Briggs and Gibson families traveled in a caravan to Charleston, South Carolina on May 28, 1951 and joined the hundreds of Blacks who stood outside the courthouse on Broad Street to hear the Briggs arguments. Then, on June 23, 1951, the District Court ruled that Black schools in South Carolina were, indeed, inferior to White schools and ordered South Carolina to equalize their educational facilities; however, they denied Black students admission to all-white schools. As a result of the latter, Judge J. Waties Waring, an eighth-generation Charlestonian done with “the false doctrine of white supremacy”, wrote an angry dissent. Included in it were the underlined words: “Segregation is per se inequality.”

On appeal Briggs v. Elliott headed to the U.S. Supreme Court where it eventually joined with four other lawsuits to form the landmark 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education. In that famous case, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional.

The Aftermath

The victory did not come without its costs for the Black people of Summerton, however. Many who signed the petition lost their jobs. Most were threatened by local whites and the Ku Klux Klan. The Pearsons spent most nights taking turns guarding their home. Joseph A. DeLaine, Sr. and his family’s house was burned to the ground.

Harry Briggs was given a carton of cigarettes on Christmas Eve and fired from his job as gas station attendant. Eliza Briggs was fired from the Windsor Motel, her employer simply telling her that the people of Summerton wouldn’t let him run his business if he kept her on. After being unable to eke out a living in Summerton in the aftermath of Brown v. the Board of Education, the Briggs left for Florida in 1957.

Still, none of the petitioners made any apologies. As Levi Pearson said, “I believe God wants me to do it. God wants me to make the sacrifices.”

The Windsor Motel

The Windsor Motel still carried on business-as-usual afterwards, even adding a swimming pool, a children’s playground, horseshoe pits, shuffleboard slabs, and a “TV in every room”. However, it was sold in 2005 and its name changed to the Economy Inn. These days, though there are a few cars out in front and a handmade sign offering rooms for $20 a night, it seems to be a shell of its former self and the once well maintained property is now over overgrown with grass and weeds. There is no online presence or number to make reservations making one believe that perhaps the motel is closed.

At the same time, the Windsor Motel’s place in history is likely too insignificant to warrant it a place on the National Register of Historic Places. Still it’s pretty interesting to see these roadside accommodations we once took for granted can sometimes have a sort of butterfly effect on the history of America in bigger ways we could ever imagine. As historian Howard Zinn once said:

“History is instructive. What it suggests to people is that even if they do little things, if they walk on the picket line, if they join a vigil, if they write a letter to their local newspaper… Anything they do, however small, becomes part of a much larger sort of flow of energy. And when enough people do enough things, however small they are, then change takes place.”

Stuckey’s – We’re Making Road Trips Fun Again.

Whether your next road trip is by car or by rail, it’s not really a road trip without taking Stuckey’s along. From our world famous Stuckey’s Pecan Log Rolls to our mouthwatering Hunkey Dorey, Stuckey’s has all the road trips snacks you’ll need to get you where you’re going.

For all of the pecany good treats and cool merch you’ll need for your next big road adventure, browse our online store now!

Stuckey’s – We’re Making Road Trips Fun Again!